May 2, 2019

As I sit in my office today, I am surrounded by reminders of hate, violence, and the politics of eradication. A few minutes ago, I finished an interview with our student paper to contextualize the recent surge in on-campus outreach efforts by neo-fascist and white nationalist groups. Before the interview began, I opened my office window on the third floor of our aged building to get some air and was further reminded of the unhealed nature of these past crimes. Today, only a few hundred feet from me, a lone student stands under a tarp reading our thousands upon thousands of names: the names and ages of victims of the Nazi Holocaust for Yom HaShoah. As the list of names drones on and the interview about campus fascists continues, I consider the litany of events that all feel so similar.

I think of the 2012 Wisconsin Sikh temple shooting, the 2015 shooting at a Black church in South Carolina, the 2017 shooting at a Quebec City mosque, or the 2018 shooting at a Pittsburgh synagogue a few hours from my community. I think of the murder of 50 Muslims in Christchurch or the shooting at a California synagogue just last week. If I keep wandering, I quickly get to the suicide attacks in Sri Lankan churches that occurred the same month. In my job as a professor focused on political violence, these events amass like scars to my psyche, each one remembered for its particular horrors, images, and death tolls. Some I have even learned about, taught, and since forgotten as their details are replaced by new tragedies, which collect like a scrap book and blur together.

The shootings at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, were both alarmingly unique and regrettably familiar. On the night of the attacks, I was asked by a journalist assigned a “terrorism beat” to provide my analysis of the shooter’s manifesto. The reporter sent me the text and the social media materials through a secure channel, and I was able to quickly locate the shooter’s video by observing far-right communication networks I routinely monitor.

After assembling the ephemera and digging into it, what struck me most was how uniquely American this particular text was, despite being authored by an Australian striking in New Zealand. The text was an amalgamation of American white power; (eco)fascism; and “traditional” racist, anti-Semitic, xenophobia. In the shooter’s text I could hear the works of Americans such as the eugenicist Madison Grant, American Nazi party leader George Lincoln Rockwell, and contemporary individuals such as William Pierce, David Lane, and Tom Metzger. Mix in Internet-8chan-meme culture humor and a nod to contemporary international fascist movements, and we have yet another diatribe from a fascist who committed murder. In the shooter’s writings I heard the refrain popularized in the Turner Diaries and repeated by white power strategists: provoke social conflict and reap the rewards of the race war.

The Christchurch shooting reinvigorated the debate about if, when, and how we should circulate, read, and discuss the writings by individuals who voice their dissent with lethal violence. We were told by well-meaning people that we should not share the killer’s writings lest we fuel further attacks. “It’s just what he wants you to do” becomes the refrain as individuals want to ensure that they are not complicit in institutional white supremacy, disguised anti-Semitic tropes, and nativist dystopias. While I understand the argument advocating limiting exposure to murders’ manifestos, it denies a central point, namely that political violence contains its own rationality, cost-benefit calculations, and strategy. These attacks are not inherently the acts of ‘crazy’ or senseless people, and while we should be sure to not amplify their voices (as they speak for a tiny portion of people), we must engage them on an ideological and rhetorical level.

In the classroom I work with my students to read texts which that make us uncomfortable or even fearful. I make it my business to read what radical socio-political movements write and would encourage others to do the same. There is a value in understanding the motivations of political violence for developing counter-narratives and community-based empowerment. Violence, including terroristic violence, aims to be communicative, and denying that message an audience does not address its underlying motivation—nor does it serve to prevent future violence. The sooner we realize this and can move past the “do we share or not share the manifesto” debate, the better prepared we can be to understand and disrupt far-right violence and build a movement of solidarity and defense that is resilient, diverse, and focused on winning.

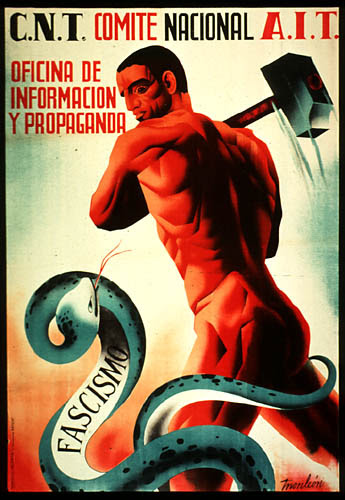

¡No pasarán!